On Art & Kitsch

And An Interview with Luke Hillestad

Luke Hillestad, Self Portrait as Polar Explorer, Oil on Linen.

“If I were an artist, I would not paint.”

-Odd Nerdrum

I.

In the public imagination, there are natural associations we tend to make with the word, “art” or “artist.” One thinks “Creative.” “Original.” “Out There.” “Expressive.” “Free.” Or “Genius.” The artist is a rebel, a rule-breaker, misunderstood in their time, even socially and politically dangerous. Artists are supposed to be unusual or challenging personalities: borderline mad, transgressors, drug users and alcoholics, smashers of taboos, colorful guests at dinner, right-brainers, effete dandies (think Whistler), tormented souls (Caravaggio, Van Gogh, Bacon), enigmatic gurus (Matisse, Warhol, DeKooning), or something akin to movie stars - spectacular public personages who are unimaginably rich (Picasso, Jeff Koons) or just plain fascinating (Kahlo, Toulouse-Lautrec). It’s a rich tableau that swims in the art lover’s head.

And we assume our culture is ultimately made better by its full embrace of art and artists of all types (even works we hate) and this general positive regard occasionally involves our tolerance, if not adulation, of the shocking, the outlandish, the incomprehensible. Today, anyone can call themselves an artist, and artists are largely given a free pass. So, the temptation for the talentless to be one is everywhere. To cite an extreme: In 2007, Guillermo Vargas Jimenez chained a dog to a gallery wall and invited the public to watch it starve. The poor creature’s feces were smeared on the wall. This is art, apparently. It’s not much of a leap from here to the banana duct-taped to a wall that sold recently for $120,000 at the Miami Biennale. Whatever: bring it on.

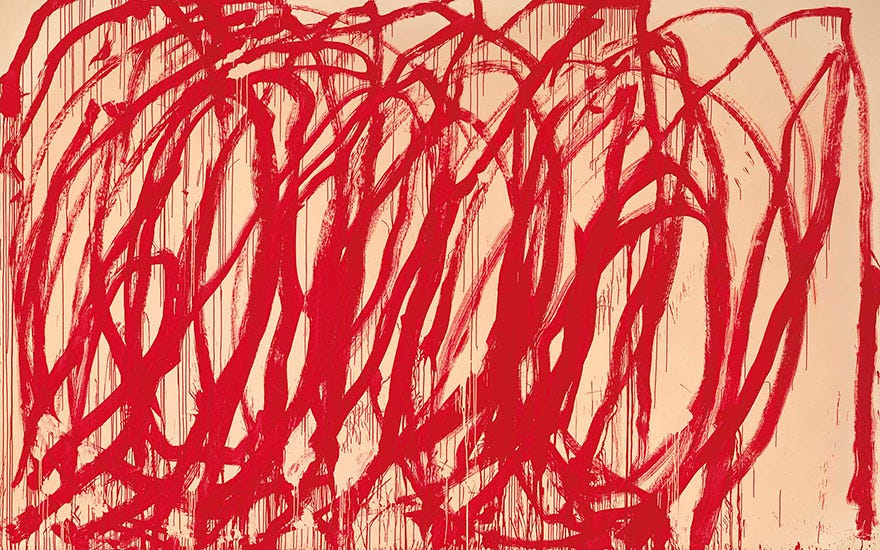

Or on the high end, observe the widely-celebrated Bacchus series by Cy Twombly, executed between 2003-2008 and worth millions of dollars, images of what appear to be the large tantrum scrawls of an unhinged third grader. Art this is, most assuredly: just look at the price. If you simply don’t “get” this work and many others like it, the suspicion is that there is something neanderthal-ish about you. Unsophisticated. That sentiment, if you will, is ironic. So, call me a Neanderthal.

Cy Trombly, From the Bacchus Series.

The term “art” is relatively new, emerging in common use only in the 18th Century at the cusp of the European Industrial Revolution. It derives from the old Latin “ars,” which in Roman times was closely linked in meaning to what we now think of as “craft” or what the Greeks referred to as “techne” - a skill. Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque painters would never have referred to themselves as “artists,” a term unknown to them. They considered themselves practitioners of a craft - painting, sculpture, architecture, drama, music, wood working, etc. - and their skills were sanctioned by guilds who demanded a demonstrated competence to practice their skills in the community - the submission to peers of a “masterpiece.” Rembrandt, for example, was considered upon entry to the Guild of St. Luke to be “skilled in the craft of painting.” He wasn’t an “artist” in the 17th Century. But today, that is exactly what we call him and his predecessors Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Titian. Indeed, all these have become archetypes of “the artist” in our modern imagination.

And they were all supposedly “geniuses,” another invention from the 18th & 19 Centuries (from the philosophies of Kant and Nietzsche). The notion of genius allows us to by-pass consideration of their hard-won skills that could only come from hours upon hours at the easel (perhaps 10,000 hours if Malcolm Gladwell is correct). The genius and artist attributions permit art historians to somehow link Picasso’s “art” and “genius” to these great old master “artists” and “geniuses” of the past, or for Julian Schnable to claim, ridiculously, Massacio as an ancestor forecasting the broken plates he crudely glued to canvas - as if Massacio and Schnabel are somehow in the same club, or Picasso’s Guernica and Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa are in the same league of narrative painting. They aren’t. The terms art and genius and their many associations in our minds muzzle most of us from saying a popular contemporary emperor has no clothes: Who are we to judge the work of an artistic genius?

It’s obvious that we’ve come a long way from craft, skill, and guild/peer-sanctioned masterpieces. The modern art era began with the rough trashing of a superb draftsman and painter, William-Adolphe Bouguereau in the late 19th Century (yes, Bouguereau could be a suffocating teacher), then the purposeful destruction of the ordered picture plane - a gift to civilization that came primarily from Leonardo da Vinci - by a clumsy draftsman, Paul Cezanne, in the early 20th. From there it got wilder and wilder - the horses were out of the barn. The question is whether the sweeping changes we’ve seen in aesthetic expression going into the modern era of art is a sign of liberating cultural progress or a signpost of decline and a reflection of deepening social anomie.

So, questions for you: Do we somehow debase human life through aesthetic expression if we abandon rendering human beings (or objects) with skill, proportion, and beauty? Is the scrambling or destruction of coherent pictorial narratives psychologically and socially damaging? Is the encouragement of free expression “liberating” or merely a sanctioning of vandalism? Modern art certainly entertains, beguiles, and can often shock and rile us up. It is indeed interesting wall decor. But is that all we can or should expect from it?

If art in our time seems like a crazy free-for-all, some contemporary painters are looking to the past for guidance and inspiration in their work. And a few of these have chosen to abandon the word “art” altogether and all of its many conscious and unconscious associations - like the need to be original. The major progenitor of this movement is the Norwegian master, Odd Nerdrum. He has a growing band of ardent followers who are now sprinkled all over the world.

As was the case with Bouguereau, Nerdrum was mocked by contemporary art critics and his fellow artists for his refusal to follow the mid-to-late 20th Century aesthetics of his time - expressionism, abstraction, abstract expressionism, neoexpressionism, conceptualism, minimalism, pop art, color field, and so on - turning his full attention and prodigious energy instead to the production of works that appear to have emerged directly from the studios of Caravaggio, Rembrandt, and Titian.

This pissed off what the painter refers to as the “Art Police” (the nexus of gallerists, museum curators, art school deans, and art critics) who, enthralled by the ideas of the mid-century American critic Clement Greenberg and the formation of the New York Museum of Modern Art, were intent upon projecting Norwegian art as equally modern and progressive as American. Confronted with Nerdrum’s old world style, careful draftsmanship, classical references and compositions, flawless paint handling, and powerful narratives, the Art Police hurled at him what they considered to be the ultimate insult to any “artist:” They accused him of being a painter of “Kitsch.” To this, the painter gamely replied: “Thank you!”

The word “Kitsch” is derived from the German word “kitschen” which originally means to coat or smear something. When modern art as we know it today was starting to hit full stride (the 1930s), “Kitsch” was appropriated as a term used to dismiss old fashioned representational painting and help undergird the rising value of a variety of modern, rule-busting schools. Traditional paintings, like those from the Renaissance through the French Academy in the 19th Century, were dismissed for their obvious emotional content, order, sentimentality, and thus their unsuitability to the zeitgeist of an advancing industrial age. The new Kitsch Movement of today, if we can call it a movement, is a radical challenge to the contemporary art. Kitsch represents the total rejection of everything we’ve come to expect from modern art and artists, and an embrace of an entirely different set of aesthetic values.

While Nerdrum and his followers laid all this out in a thick book, I thought we should talk directly to a self-proclaimed “Kitsch Painter.” I know one pretty well.

II.

One day ten or so years ago I was in an art supply store in Minneapolis standing at the checkout counter. The clerk, a loquacious guy, was chatting me up. “What kind of art do you do?” he asked brightly. I replied that I’m really old fashioned; I want to paint like Titian. “Huh!” he exhaled. I asked him if that seemed strange to him. “No. You should meet Luke Hillestad,” he said. “You would like his work.” And with that I was out the door.

I can’t remember how I found Luke, but it was probably somewhere on the Internet. I hunted him down to a studio he had fashioned for himself in the cramped attic of a Minneapolis church. A not-quite-starving oil painter at that time, I found him to be genial with a razor-sharp intellect and passioned ideas about painting. We went out and I bought him coffee. And a friendship began.

Luke now lives in the small town of New Ulm, Minnesota, but shows at the Copro Gallery in Los Angeles and at the Flanders Gallery in Edina, Minnesota. Check out his Website. With COVID, we see each other less frequently, but in this Spring of 2022 I thought I would visit my friend and have another conversation about painting. We decided to invite all of you into it.

III.

KD: Hi there, Luke!

Luke: Keith! Good to see you.

KD: What are you working on?

Luke: As you might guess*, some works exploring motherhood, nurturing, some with mythological references, that sort of thing (*Luke and his wife, Michelle, recently had their second child). I just did a show on the theme of water called “Waterborne.”

Luke Hillestad, Sea Offering, Oil on Linen

KD: Extraordinary.

Luke: Thank you!

KD: You know, whenever I look at your work I think about the remark that is often made that great painters are detected in childhood.

Luke: Thanks for the compliments on the painting. By the way, anything you would change?

KD: Not a thing! About your childhood…

Luke: I remember my dad bringing home a Midwest Art magazine after work. I liked the pictures of eagles flying above waterfalls in it and I made some of my own watercolor paintings of this theme as a child. We also visited the (Minneapolis) downtown studio of the classical painter, Robert Olson. He was a family friend. I soaked in his studio environment - his tools, painting surfaces, and his models I saw up close gave shape to the idea that I could be a painter. I am grateful to my family for their encouragement.

KD: Something similar happened to my daughter when she was only three years old seeing a violin performance and then just wanting year-after-year to play the violin until we caved and finally got her one.

Luke: Yeah, something just clicks with some kids, doesn’t it?

KD: Do you think you were born with a talent for this?

Luke: Some people have what you’ve heard Odd Nerdrum call “The Golden Ticket.” For whatever reason, things easily click for them when they choose to paint. However, people with and without this ticket have both done exceedingly well as painters. Some have the ticket but don’t have much love for painting. In this case, those with love may go much further.

KD: The words “talented” and “original” are often used together to describe famous painters in history. Is being “original” something you strive for?

Luke: Originality is not something I strive for, but I don’t reject it. Certainly some collectors consider originality to be valuable. Used this way, it is often a romantic term for branding. But if by originality we mean “devoid of influence,” it is a puritanical and empty goal for the painter.

KD: And an unnecessary mental burden, perhaps. Spinning your wheels trying to rid yourself of influences sounds exhausting.

Luke: I prefer to ask myself to make the most meaningful images I can imagine. This is more motivating to me.When the ideology of originality stands in the way of us creating meaningful images, culture is lesser for it. The best distinction is one of quality that comes from an embodied commitment to what you love.

KD: If I’m following you correctly, what you’re saying is: Release yourself from the burden of originality in your studio practice and focus on personal meaning, on love.

Luke: Yes.

KD: What’s the most beautiful figurative painting you have ever seen?

Luke: You’ve just reminded me that I still haven’t seen Titian’s painting, Nymph and Shepherd in Vienna! Perhaps I will get to see it in person this decade and that will become my favorite in 2032.

I have seen both of Leonardo’s St. Annes (* note: the cartoon in the National Museum in London and the painting in the Louvre) and the one in the Louvre is my favorite, my first impression of it anyway. It was glowing, bold, earthy, and alien. The mountains were distant and the familial love was so close. It was life seen from a heavenly perspective. I was comforted and energized. Everything, quirky as it was, was in the right place. My senses were already heightened having been through the Louvre, but this iconic treasure blew open my sensitivity and my heart filled with possibility.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child With St. Anne & St. John, Cartoon in Charcoal and Chalk on Paper, National Gallery, London.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child With St. Anne and St. John, Before and After Cleaning. The Louvre.

KD: When was this?

Luke: In 2008 and then again in 2012. Unfortunately, in 2011 the Louvre’s curators and restorers undertook a brown-phobic and ageist “cleaning” which really affected the painting and brought the cartoon in closer competition for me. We’re learning that, with many paintings, restorers have removed layers of glaze that the painter intentionally added. I still consider my first impression of St. Anne when I think of the most beautiful painting in the world.

KD: How has St. Anne influenced your own work?

Luke: I carried this inspiration into my painting, Swamp Mama. I wanted the mother and child nestled into the murky womb of the wet earth, next to a tree struck down by the sky god. The piece is a nod to the story of Danae. I like the layout of the contrasts and the diffused light. It is familiar and otherworldly. I haven’t come closer to creating balance between chaos and order.

Luke Hillestad, Swamp Mama, Oil on Linen

Keith, what’s your favorite painting?

KD: You know, I’m such a Titian guy. My favorite is his Entombment in the Louvre.

Tiziano Vecelli, The Entombment, The Louvre.

People often miss this stunner because it’s in the same room as the Mona Lisa, or was when I was last there. What I find so incredible about this work is its unequalled portrayal of human grief, the suffering attending an inexpressible loss. The face and figure of the Virgin is a universal stand-in for the quaking frailty that accompanies the death of someone you deeply love. She can barely stand up from the weight of this moment. And the limp Christ, a figure powerful yet sagging, is being caressed as much as transported. I can’t look at this without tearing up, even in reproduction.

Luke: That’s a spectacular masterpiece.

KD: OK, a more mundane question. Everybody asks painters, particularly those working in realism, how long it takes to produce a painting. Do you hear this a lot? Do you have an answer for this? Or is the question just a stupid one? Why do you think this always gets asked?

Luke: It’s the most frequent question! I usually say a month. But the truth is, sometimes it’s four years. I think people ask because it’s obvious that it takes a very long time and they want to know if the career we have embarked upon is as absurd as it seems.

KD: I think they’re jealous and actually would like to do this, but wonder if they would have the time, the patience, and how it might conflict with other priorities.

Luke: That’s probably more true.

KD: You work with a limited palette. Only four basic colors. Why?

Luke: I look around. We live in a valley between the Cottonwood and Minnesota Rivers in a town filled with brick homes. We take ritual walks through forests of old trees and spend most of our evenings amidst candlelight. I use the Apelles palette of black, white, yellow and red. This ancient recipe seems natural to me and the mixtures from them provide more than enough range for the colors I need to describe a world that has meaning to me.

KD: You describe yourself as a “Kitsch Painter.” In the U.S., Kitsch is usually reserved for cheap, garish works that you might find in flea markets. I remember well seeing a portrait of Elvis in a junk shop painted in Day-Glo paint on black velvet. Many people think of Kitsch that way. What are they getting wrong? Can you explain Kitsch philosophy and its importance in contemporary painting?

Luke: First, the Kitsch maker is earnest. They sincerely want to make something “nice.” The Day-Glo painter of Elvis probably loves Elvis. If it is made ironically and purposely in bad taste, like with a wink, well then it is “Camp.” Camp is Kitsch’s “cousin,” laughing at bad taste while swimming in it.

Yes, the word Kitsch is used to point to low quality, still this is not the essence of the word. Poorly-made art which is not sentimental is not Kitsch. Furthermore, art critics repeatedly refer to painters like Repin and Bouguereau as examples of high quality Kitsch. Kitsch, essentially, is sentimental craft. Rembrandt’s Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph is more sentimental than any lawn gnome or romance novel cover, for we are more sentimental toward the image that portrays more believable emotion. This is “High Kitsch.”

KD: The higher the Kitsch then, the deeper and stronger is our emotional response to the image. Like my reaction to the Louvre’s Entombment, or your response to St. Anne. I remember Odd Nerdrum telling me that he used to challenge his students to paint an apple, and the one who got the top prize would be the painting that most made Odd ravenous to eat it!

Luke: That’s a great exercise!

KD: A ravenous craving is a strong emotion.

Luke: Anyone who has tried to paint a face that evokes sentiment knows how difficult it is. It feels impossible, even without the haunting possibility of being labeled Kitsch. Nearly every attempt is unsuccessful, and therefore “Low Kitsch.” The cultural stigma (to the Kitsch label) walls off many who would otherwise attempt the wondrous feat of crafting a believable emotional expression. Therefore anyone attempting sentimental craft in our time and our culture must, as they initiate themselves, go through Kitsch in order to make a masterpiece. Appropriating the word Kitsch transforms this wall into a doorway that can lead to their best work. It is a classical painter’s term for humility.

KD: In the last ten years, there seems to be a revival in realism, sparked or sustained perhaps by the Atelier Movement’s promotion of “classical realism.” Have you attended an atelier? Do you see Kitsch painting as a branch of classical realism, or something entirely different?

Luke: A Masterpiece is a wonder despite its flaws. Like a lover. If there are ateliers that hold up drama and poetry in painting as values, then they are in the same stream as Kitsch. But I’ve seen many ateliers that hold up draftsmanship much higher than a gripping story.

KD: You read a lot of philosophy, particularly the aesthetics of Aristotle and Kant. Why is this important to you?

Luke: Aristotle held high the skills it takes to make a story that holds our attention. Kant, or maybe it was Nietzsche, had the high concept of the inborn “genius.” These two seeds-of-thought birth value systems as dichotomous as Kitsch and Art. I noticed in Kant’s writing an attitude that I see in the art world that de-motivates me. He still reverberates in cliched mantras like “be yourself” or “wait to be inspired.” I think of Kant as a googly-eyed art critic who, not a painter himself, describes the Artist as he romantically imagines genius to present itself. Not about any universalized practice which he observed emerging from the studios of the masters.

KD: Say more about your preference for Aristotle.

Luke: I like that Aristotle is methodical and writes in specifics. We can concretely evaluate the advice he gives to poets and painters in his “Poetics.” In it he is like an AB tester for the desires of an ancient spirit. He is a scientist who has tested what elements make for the most gripping stories. I do not have a favorite painter or storyteller who credits Kant as an inspiration, but many of my favorites point to Aristotle. More than a popularity contest, Aristotle has proven useful, while Kant is more subtly oppressive.

KD: Oppressive?

Luke: Say you are feeling low. Nothings seems to be going right. You see brilliant works by contemporaries and past-masters and conclude: “I am just not a genius.” Ideas that you either are or are not a genius can feel euphoric when things are going well, but downright devastating during our lows.Even if someone could let go of their ego, Kant offers nothing to the craftsperson. As a good psychologist would tell us, personal progress comes, not by dwelling in broad romantic imaginings, but with specific actionable steps.

KD: Besides Aristotle, would it be fair to say that the other biggest influence on your painting is Odd Nerdrum? What did you learn from him? If he visited your studio today, what challenges would he present to you?

Luke: Yes, that is right. Nerdrum is my biggest influence. He is remarkably disciplined and full of love. His advice to me was always specific to a painting, but in nearly each instance it was geared toward heightening the drama. It is rare to find that value in a teacher and no one has a better sense of how to paint drama than Nerdrum.

I remember talking to Nerdrum about the lack of modern masterpieces. Odd imagined that if the last century had just four more people as skilled and productive as Rodin, then we would look back on the 20th century as a golden era. You see, without Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian, we would not have what we now recognize as the High Renaissance in Europe. This level of quality is undeniable. It is the result of just a few individuals embodying an absolute dedication to what they love.

The Nerdrum School is devoted to the development and recognition of this kind of mastery. They have created an environment that is full of the best in craftsmanship and story telling. They surround themselves with gorgeous music, epic poetry, and a spirit of diligence. After a couple of weeks with Odd, it becomes clear that this astounding oeuvre is no accident. It’s hard work. The result of daily choices. I’m proud to locate myself squarely in that practice and tradition.

KD: And so, unfortunately, we must come to the end for now, Luke. Thank you. And perhaps see you in Vienna to look at that Titian!

Luke: That would be a fine thing, indeed, Keith.

KD: I just hope you don’t have to push me around the museum in a wheelchair. In 2032, I’ll be 82 years old! Perhaps you’ll paint something as good as that Titian and I won’t have to travel that far to see a masterpiece. Happy painting.

Tiziano Vecelli, Nymph & Shepherd, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

-Spring, 2022

REFERENCES

Odd Nerdrum, et.al., Kitsch: More Than Art. Schibsted Forlag, 2011.

Clement Greenberg, Art & Culture. Beacon Press, 1971.

I love these posts. I learn so much that it eases the regret I have for sliding through the art appreciation elective I took in college. A thought for you and Luke to ponder in your next conversation (which I hope also is public): In an increasingly angry America, is there a role for art to bridge some of the chasms? Everything from sports to literature divides us. If the two of you can have a provocative conversation that ranges from Day-Glo Elvis velvet paintings to Titian, can you engage pols in a conversation about art that could be the common ground for intense partisans?