I.

The pride of the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City is the painting, St. John The Baptist in the Wilderness by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610). There are at least three essential attributes of great figurative painting, and they are all here in abundance. One is the uncanny sensation that a static figure in the picture is about to move or speak. This demands from the painter a convincing rendering of human anatomy and gesture. The second is the presence of a solid compositional structure and color scheme that pleasingly orders the visual experience without sacrificing the pop of surprise or mystery. The third is the presence of narrative that heightens awareness of some universal theme, value, or moral imperative that draws on our emotions. Even within the small confines of a self-portrait, like Rembrandt’s masterpiece in our National Gallery, great pictures should tell a huge story and cause us to feel something. The Nelson-Atkins’ pride in its Caravaggio is justified; this is one of the most significant paintings on American soil. A friend of mine who works at the museum told me he was instructed that in case of fire, rescuing “The Caravaggio” is the top priority. It is the museum’s wedding album, so to speak.

The figure in this work is rendered with such extreme chiaroscuro that one observer commented that it looks as if the saint is being struck by lightening. Caravaggio’s approach to this icon of Christianity is radical on several fronts. Note the disorienting youthfulness of the model, accustomed as we are to seeing The Baptist as an older, grizzled denizen of the desert; or, conversely, as the chubby infant cavorting with Baby Jesus about the knees of the seated Virgin in some Arcadia. This seems a sullen teenager: perhaps an identity crisis is here: is the Tenuousness of the Self the artist’s central theme? The saint’s eyes are drowned in deep shadow which makes you increasingly desperate to see them. The bright figure is set before a dark background of oak leaves and is enfolded by elegant red drapery that would be equally at home in a resplendent Rubens or an aristocratic portrait by Jacques-Louis David. These unusual compositional elements in a Biblical painting rivet your attention from far across the room where the painting hangs. A closer view of the picture reveals a tuft of camel or goat hair grazing the saint’s smooth upper thigh, a wildly provocative touch that prompts us to consider whether the narrative involves spiritual awakening or sexual. Possibly both.

The model was likely a boy Caravaggio plucked from the streets of Rome, the tactic of a painter intimately familiar with them, and we can’t rule out a male prostitute given the painter’s side hustle as a pimp and the abundance and variety of sex workers in the Rome of the early 1600s when this painting was executed. On a recent museum visit, I found myself wondering for a long time about the actual circumstances of Caravaggio’s violent life and how much of it affected his paintings. Do we best understand his works as escape from a troubled existence or a manifestation of them? In his best pictures, Caravaggio manages to keep light and darkness in an exquisite equipoise, but it is his darkness, to paraphrase Milton, that he makes most visible in his oeuvre. His paintings invariably unsettle, even a “sunny” piece like The Basket of Fruit where he drops in early traces of spoilage and sets the basket ominously out beyond the table’s edge. In Caravaggio’s works, there is always something spooky, prohibitive, or dangerous lurking about. Death is always in air, or indeed often placed at center stage.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Basket of Fruit, Oil on Canvas, 1599.

Caravaggio’s father, a Milanese stonemason named Fermo Merisi, died of plague when the nascent painter was only six or seven years old. How shielded or exposed Caravaggio was to this gruesome event is something we will never know (the plague killed other members of his family as well). While today we benefit from the concept of trauma and understand its magnification in children, these ideas were obviously unavailable in 16th Century Europe. What was readily at hand was the Church. “Treatments,” if we can call them that, consisted of palliatives issued from religious images, prayers, and rituals. It probably didn’t help psychologically that the leading framer of Caravaggio’s sudden loss, the architect of his early world, happened to have been the most ferocious leader of the Counter-Reformational Church one could possibly imagine.

Cardinal Carlo Borromeo (1538-1584) was the tip of the spear of the Church’s efforts to halt the spread of heresy from the Protestant North into the Italian peninsula. He was appointed Archbishop of Milan in 1565. Unlike the “remedial” approaches to heresy and sin preferred by the Spanish Inquisition (e.g, thumb screws), Borromeo’s strategy was grounded in prevention, a sort of “public health” approach to the problem. His special passion was rooting-out anodyne occasions for sin, focusing on the “ground” upon which any “seed” of heresy might subsequently fall. For this he conjoined a restless, imaginative fanaticism with a calm detective’s eye for detail. Women and men were separated at Mass by large partitions to foreclose on any opportunity for temptation. Strict dress codes were the order of the day. A telling detail: confessionals were re-designed at Borromeo’s precise specifications to prevent the possibility of a confessor’s feet inadvertently (or otherwise) touching those of the priest under the internal partitions. In Milan, at that time a city of fifty thousand people, the determined man seemed to be everywhere, perhaps like Mao’s presence in Beijing four hundred years later but without the ample flesh and enigmatic smile. I picture the Archbishop as the severe, thin commander of the Death Star in the original Star Wars movie, capable even of ordering Darth Vader around.

When secular authorities abandoned Milan during the plague of 1576-77, the Archbishop took over the city’s civil governance. A type of Marshal Law ensued. There were compulsory evening vigils in the receding light of the cavernous Milan Cathedral, and conscripted attendance at daylight religious processions the Archbishop led through streets that were then choked with blotched corpses and the dying left sprawled outside on the stone pavement by their fear-stricken families. Borromeo was also a fan of pilgrimages to the Sacro Monte di Varallo outside the city. Sacro Montes (there are several in Italy) are small chapels set on hillsides linked by pathways, each chapel containing life-size polychromed statues illuminating scenes from the Bible. Lit by candles, it is easy to deduce the hold these might have had on the imaginations of people consumed by fear, particularly on children having just walked through Milan’s ghastly streets, then contemplating the Sacro Monte’s diorama devoted to The Massacre of the Innocents. In a city of mass death, Counter-Reformation hysteria, and processional dirges orchestrated under the cadaverous mien of the omnipresent Borromeo would make a scarring impression on everyone living there. It seems inconceivable that boy-Caravaggio and his grieving mother were sparred any of this. Out of the communal horror Caravaggio’s life became a dizzying admixture of belligerence, impulsivity, crime, depravity, and graphically painted images. How could it not?

Caravaggio’s mother, Lucia Aratori, placed her teenage son in an apprenticeship with a mediocre Milanese painter, Simone Peterzano. Deviating from common practice in master-apprenticeship arrangements, Peterzano charged fees to Caravaggio’s family even though the apprentice, like all the others, was expected to perform numerous unpaid duties in return for instruction. There is some speculation that a rich and powerful Marchesa, Costanza Colonna, a regional benefactor of the Merisi family, picked up the tab. These unusual circumstances make us wonder if the teenager was “dumped” by his mother who perhaps could no longer handle her difficult son nor afford to send him anywhere without significant help. It could be that Peterzano anticipated an unusually fraught assignment so charged her for it. From his teacher, Caravaggio learned very little and was soon drawn into a circle of street toughs hanging about the alleyways surrounding Peterzano’s studio. In a few years, a serious crime of some sort occurred, and staying one step ahead of the law, the fledgling painter abandoned his apprenticeship and fled to Rome.

As a man who seemed never to be at a loss, in Rome Caravaggio managed to secure part time work as an assistant painter to several established artists, and he picked opportunities strategically to get his own work exposed to the powerful art patrons of the city, particularly those in the upper echelons of the Vatican. They saw something fresh and exciting from this new guy crashing in from the North onto Rome’s frenzied art scene. Incompletely trained and de-regulated by a hair-trigger temper, Caravaggio nevertheless begins to paint magnificently and with obvious discipline. He moves into a spectacular palace (home now to the Italian Parliament) at the invitation of a Cardinal, Francesco Maria Del Monte. This erudite benefactor, a friend of Galileo’s and an art connoisseur of rarified taste, was the closest thing to a father figure Caravaggio ever had. But as in Milan, the painter slipped easily into the demimonde of thugs and various low-life in the streets. As skilled with a sword as he was with a paint brush, Caravaggio killed a rival in a sword duel. Not even the powerful Del Monte, who routinely plucked Caravaggio out of trouble, could save him this time from the authorities.

On the run again but now with a papal price on his head, Caravaggio sought refuge in far flung Colonna estates and remarkably kept producing paintings all during his flight from Rome. He somehow managed to secure passage to Malta (Costanza Colonna’s brother happened to have been admiral of the Maltese Navy). Quickly sizing up the opportunities on the island, Caravaggio ingratiated himself with the Grand Master of the Maltese Knights by painting flattering portraits of the vain man and his top officers. For this, The Grand Master kept the Pope at bay, as Caravaggio shrewdly knew he would and as was the Grand Master’s general custom. Caravaggio then painted his most profound work (and the only one he ever signed - in the red “blood” on the floor under the saint’s neck): the gloomy and enormous Beheading of St. John for placement above the altar in the Oratory of St. John (The Knight’s patron saint). This painting was undertaken as an entrance fee of sorts to Maltese knighthood. Its spare, grim depiction appealed directly to the sensibilities of the Grand Master and the ethos of the legendary Knights, who saw themselves as the last defensive line of Christendom, a Delta Force if you will, holding back the evil, advancing Moorish horde from crossing the Mediterranean.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Beheading of St. John, Oil on Canvas, 1608.

But soon after Caravaggio’s knighthood investiture there was a drunken, violent episode and an enraged Grand Master threw Caravaggio in prison. He escaped (how remains a mystery) and made his way to Naples by way of Sicily, securing patrons and their protection along the way (his fame had grown), producing masterpieces for Sicilian churches and villas all the while stalked by vengeful Maltese Knights and the now freed-up Papal Police. Running around under a sentence of death never seemed to slow the production of paintings or arrival of Church commissions. Perhaps the Pope was never really all that serious about having the painter’s head and rich patrons knew it was so but kept that to themselves. Reports of Caravaggio’s physical and mental deterioration suggest his perception of mortal threat was very much alive in his mind.

Reaching Naples, an exhausted and paranoid Caravaggio hid out again in the Colonna palace. But his self-destructiveness eventually gained hold. In the early morning hours after a night of debauchery in a notorious bar cum sex club, he was severely beaten (probably by Maltese Knights catching up). Recovering from wounds, he got word that strings were being pulled in Rome to secure a papal pardon and that a few of his paintings would be needed to help grease the skids. A famous Caravaggio self-portrait as the decapitated Goliath had previously been sent to Rome during his earlier flight, perhaps as mollifying humor (“You see, Your Holiness, you already have my head.”). Several of Caravaggio’s works, including Goliath, had caught the eye of the acquisitive Vatican Justice Minister, the Pope’s corpulent and corrupt nephew. He wanted more of them. So, still reeling from head gashes, Caravaggio departed Naples in what was to become a frantic, chaotic quest to hand over some works to the Vatican. He sailed from Naples with his cargo down the Italian coast to a Roman port city where, unfortunately, he picked a fight with a customs official and was thrown in jail. The boat he came on left with his paintings in its hold, back up the coast on return to Naples. Released from jail, Caravaggio scrambled up the coast by land to try and catch up with the boat, rushing forward in the sweltering July heat. He collapsed finally on the deserted, swampy beach of Porto Ercoli and died. His body was never found, but the Vatican, after a brief squabble over ownership, eventually got the paintings.

How do we reconcile Caravaggio’s short, disordered life with the sublimity, craftsmanship, and volume of its artistic output? Could we have had the great painter - the giant of the Baroque, the supreme master of tenebrous light - without the childhood of Black Plague, the tenor of Counter-Reformation, the father’s untimely death, Borromeo? Could we have had it without the foul taverns of Rome and dark alleyways, the thuggery, gangs, and lethal violence? I think not. Take a long hard look at his supreme masterpiece, Matthew Called. It is a crude setting he chose, one that we might describe today a “biker bar.” There’s nothing at all like this in the art that preceded him. It is a setting Caravaggio knew only too well. Christ here could just as well be a bartender confirming customers’ orders.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Matthew Called, Oil on Canvas, 1599-1600.

These circumstances seem essential now to our understanding of his uniquely dark aesthetic and unwashed realism. A more challenging question is the artist’s legacy. Of what lasting relevance is Caravaggio’s work to Western painting other than its manifest craftsmanship and his novel use of strong chiaroscuro? How does it relate to contemporary painting, to our times as much as to his?

II.

More than two thousand years ago, Aristotle in his Poetics introduced civilization to the term, “Katharsis,” his meaning becoming nearly identical to Freud’s “Catharsis” in the development of psychoanalysis in the 20th Century. For both men, katharsis or catharsis refers to a deep emotional cleansing or purging; for Freud this was a major goal of psychotherapy and for Aristotle it represented the highest calling in art. While Aristotle concerned himself primarily with the art of drama, his notion of katharsis can be found in our responses to many different art forms: a verse from Emily Dickinson or Yeats, a leap from Baryshnikov; the opening of Sibelius’s Violin Concerto, for example. In visual arts, katharsis inevitably occurs when one first comes upon Michelangelo’s Pieta in St. Peter’s or, say, Titian’s Entombment or Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa in the Louvre. In my hometown, this happens to me when I pay a visit to Rembrandt’s Lucretia in The Minneapolis Institute of Art. Your heart breaks, or something moves inside you, an emotion often difficult to describe in words. Not all works of art do this, but the best ones invariably do. As both Aristotle and Freud intuited, katharsis/catharsis is profoundly restorative.

Take the unusual case of the comedian and actor, Bill Murray. Once engulfed in personal despair, he accidentally stumbled upon Jules Breton’s Song of the Lark in the Chicago Institute of Art, a moment that literally saved his life. Experiencing a great painting can and should be like this. But the experience has become increasingly rare in modern and contemporary painting. Imagine had Mr. Murray instead run into a Mondrian, a Picasso, a Julian Schnabel, a Basquiat, a Jeff Koons, or a Damien Hirst: he probably would have continued to make his way out the back door of the museum and thrown himself, as he originally intended, into Lake Michigan. And that is because much of what contemporary art offers is entertainment - no, more often an ironic concept of entertainment - and not what I would call cathartic engagement in the Aristotelian sense. Entertainment can only aim at escape, amusement, a beguiling puzzle. It often requires little discernible skill to produce (e.g., Jeff Koons proudly proclaims he cannot draw). Because it doesn’t demand much skill, contemporary works like these have to be intellectualized in order to be taken seriously, something that is fodder for many a joke in The New Yorker. Entertainment is enjoyable, even thrilling, but it can’t save your life or help you extract a deeper meaning from it. The danger facing us in contemporary art is that we are losing even the very idea that catharsis is possible when looking at a painted picture.

Jules Breton, The Song of the Lark. Oil on Canvas, 1884.

Serious times, like our’s and Caravaggio’s, and certainly for Mr. Murray, call for a serious art. We seek in it something more fulfilling than shock, irony, buzzy wall decor or amusement. We crave an emotional, existential anchor. As the critic Peter Schjeldahl recently observed about today’s art and the horror of the COVID 19 pandemic, the abstractions and conceptual works we have become so accustomed to simply lack the “heft” of the Old Masters. Fortunately, there are contemporary painters who understand this. There is, shall we say, a Derriere Garde afoot, removed entirely from the modernist canon, going in the other direction, and they are producing great paintings, not just entertaining ones.

Take, for example, the works of another Italian, the contemporary painter Roberto Ferri. For one thing, his paintings look like they were completed under the direct supervision of Caravaggio. As in the Nelson-Atkins’ St. John, Ferri fuses spiritual longings with sexual ones, but then adds a strong dose of startling fantasy that would have been suppressed in Caravaggio’s time although hinted at in several of the old master’s works. One of Ferri’s paintings, Resurrection, leaves you spellbound. If you lost someone to COVID or in a mass shooting, stumbling upon this image would bring you to your knees - in a good way.

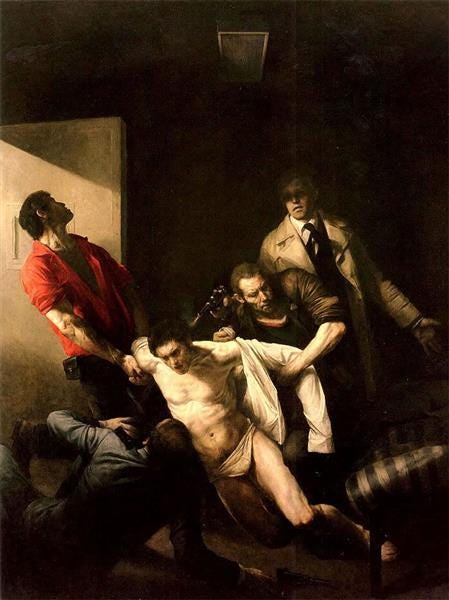

Or take the large, apocalyptic narrative paintings of the Norwegian master, Odd Nerdrum. He entered the art world with a loud bang in 1978 with his distinctly Caravaggist work, the stupendous Murder of Andreas Baader.

Odd Nerdrum, The Murder of Andreas Baader, Oil on Linen, 1978.

As Nerdrum was introducing himself to the world, the art world responded largely with visceral scorn, not unlike the howls of outrage Andrew Wyeth had to endure earlier when Christina’s World was “allowed” into The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Over time, Nerdrum seems to have left Caravaggio’s style of realism in favor of those of the late periods of Rembrandt and Titian. Like Titian (e.g. The Flaying of Marsyas), Nerdrum can be brutal in both subject matter and paint handling (e.g., Self-Portrait in a Boat; The Cannibals). But he has also provided us with rapturous works (e.g., Drifting) and elegaic ones (e.g., Mother; The Egg Snatchers) that are luminous, poignant, and breathtakingly beautiful.

Odd Nerdrum, Drifting, 0il on Linen, 2006.

Nerdrum and his followers have been the most vocal in rejecting the underpinnings of the modernist aesthetic. The precepts of modernism were set forth in the mid-20th Century by the art critic Clement Greenberg, then reified in the formation of MOMA under its longtime director, Alfred Barr. Rockefeller money helped as, it’s rumored, support from the CIA who had a Cold War mission to put forth a uniquely American vision of painting overseas. The foundations of modernism have deeper roots stretching back to the philosophical writings of Emanuel Kant in the late 18th Century. In his Critique of Judgement (1790), Kant asserted that art should reflect its specific time-spirit or zeitgeist and, since change is endemic in history, we should demand complete originality from the artist. Also, the art of its time should demand no more from the viewer than a “disinterested interest.” This is a long way from Aristotelian ideas about aesthetic universality, adherence to immutable artistic standards, and the aim of katharsis. In Nerdrum’s view, the commercial success and cultural hegemony of modernism has resulted in a debasement of painting, a lowering of expectations, and the forsaking of skill. Thus we can take in his apocryphal (some would say self-aggrandizing) work, The Savior of Painting that, one assumes, says it all.

Odd Nerdrum, The Savior of Painting, 2011.

III.

Ferri; Nerdrum; the Swedish painter Nick Alm; the Americans Luke Hillestad, Daniel Sprick, Jacob Collins; the Chilean Sebastian Salvo - even the contemporary painters of the American West (e.g., Mark Maggiori) - are largely working off to the side of the showy biennials and prominent coastal galleries. A few feel stymied by what Nerdrum calls “the Art Police:” the nexus of gallerists, auction houses, critics, art school deans, and curators - the guardians of the Kantian Universe. Setting aside insider art polemics and a tiny hint of conspiracy theory in Nerdrum’s contention, like the Romans who first came to see Caravaggio’s paintings in their churches, it is simply refreshing now to see skillfully-produced, emotionally engaging compositions rooted in a realism in which we can readily recognize ourselves and each other. We, like those in 16th Century Italy, are living in a threatening, tumultuous time. The revival of realism and Old Master sensibilities might not fit the modernist zeigeist, but the new paintings seem, much like Caravaggio’s, timeless.

Caravaggio didn’t have any illusions about who he was. Supposedly a priest once admonished the painter for failing to bless himself with Holy Water when leaving church. “Holy Water is for venial sins, Father,” he allegedly replied. “All of mine are mortal.” The magnificent works he left to us are penance enough. And if, in 3o years, we have new paintings anywhere near this good, they will attenuate the remembered suffering of today and be a compelling reflection of it. Let’s hope for that. If we can survive a pandemic and diminish the forces that now threaten us existentially, we will surely benefit from painting undertaken in the Old Way, works that offer us cathartic restoration. Paintings with heft.

-Summer, 2021

_____________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Andrew Graham-Dixon, Caravaggio: A Life Sacred & Profane. Norton, 2010.

Helen Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 1999.

Peter Robb, M: The Man Who Became Caravaggio. Duffy & Snellgrove, 1998.

Taschen (Publishers), Caravaggio: The Complete Works, 2007.

Aristotle, Poetics. Penguin Books, 1996.

Emanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment. 1790.

Peter Schjeldahl, “Mortality and the Old Masters.” The New Yorker, April 6, 2020.

Odd Nerdrum et.al., Kitsch: More Than Art. Schibsted Forlag, 2011.

Thank you!!!

Thanks for spending the time we did in Gallery P15 at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Enjoyed experiencing Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness with you.